Naima Joseph, MD

Dr. Naima Joseph is a Global Women’s Health Fellow at BWH. Through her research and clinical practice around issues of cervical screening, Dr. Joseph is contributing towards improving cancer related morbidity worldwide and improving healthcare for women.

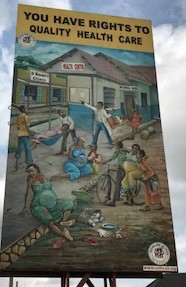

On Kampala-Masaka road, approximately 420 kilometers from Kampala, Uganda’s capital city, lies the Equator. The Equator is in Kayabwe, a bustling village in Mpigi District, and is a known as a destination of sorts. There, you can conduct scientific experiments to estimate the Coriolis effect, or earth’s rotational forces on weather. You can weight yourself and find that you are one lb. lighter on either side. And of course, you can buy souvenirs, or a latte. My favorite stop along the Equator is a seemingly innocuous billboard that boldly proclaims, “You have rights to quality health care.”

The sign is a reminder that there is a work to do in terms of improving Uganda’s health system and maximizing population health. Despite record investment over the past ten years, Uganda’s health care performance is ranked 149th out of 191 nations by the World Health Organization. While investments have prioritized communicable diseases, such as HIV, TB, Malaria, and maternal disorders, deaths from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have increased by almost 50% in the past 10 years. The probability of dying between ages 30 and 70 from the four main NCDs (cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease) is 21%. The government may recognize the right of its people to quality health care, but has yet to develop a multi-sectoral coordinated response, protocol, or policy, around prevention and management.

That doesn’t mean community interest is lacking. Locals in Nykabare, a parish in the south-west district of Mbarara, will freely discuss their concerns. Top concern? Food security. Health, a close second. To that end, community leaders have engaged the local health center and tertiary referral hospital to meet their needs, specifically requesting not just HIV screening, but screening for NCDs. As an obstetrician-gynecologist, and a Brigham & Women’s Global Women’s Health Fellow, I have been working with the Department of Gynecaelogy and Obstetrics of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH), to meet the demands of its surrounding catchment, namely improving cervical cancer screening availability and quality.

The cervical cancer prevention team at MRRH consists of Dr. Ronald Mayanja and Nurse Alexcer Namuli. The two of them educate and screen over 200 women annually in their clinic, and through screening campaigns throughout the southwest region of Uganda. Despite their exhaustive work, they see, almost daily, a woman with advanced cervical cancer. “When you see her in front of you, she is not just cervical cancer,” Nurse Alexcer told me. “She is a missed opportunity, she is a preventable outcome, she is the center of her community.”

Indeed, cervical cancer is entirely preventable, but it is the leading cause of cancer related deaths among females in Uganda. A 2014 survey by the Uganda Cancer Institute revealed that only 30% of women had ever received cervical cancer screening and that less than 70% had completed appropriate follow up. Almost all cases of cervical cancer can be prevented with early diagnosis of premalignant lesions followed by treatment of those lesions; however, in Uganda, many women are inappropriately screened by either conventional cytology-based screens or visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA). Screening is only effective if women are screened appropriately and if screen positive women receive treatment of precancerous disease.

Dr. Mayanja and Nurse Alexcer offer their own clinical insights for inadequate screening: women’s fear of pelvic exams, women’s inability to access and pay for screening at health center clinics, and provider errors in screening.

However, these passionate providers believe more can be done to improve the quality of cervical cancer screening and are working with our team to launch self-sampled high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing for screening. HRHPV testing has been recommended by the World Health Organization as a preferred screening strategy when feasible. HrHPV testing is more sensitive than cytology, has a higher negative predictive value for precancerous lesions than cytology and VIA, has less inter-observer variability than VIA, and has a favorable cost-effectiveness profile versus cytology or VIA. Finally, hrHPV testing remains efficient in settings with high HPV vaccine penetration, and more sensitive in a population with high HIV prevalence. Importantly, hrHPV testing can be performed by self-sampling, averting the logistical and human resource challenges associated with clinical exams, as well as increasing availability of screening to remote women.

However, there is limited experience on implementation of hrHPV self-screening in LMICs, and an important unanswered question for the field is whether community-based self-sampling hrHPV testing can meaningfully improve access to cervical cancer screening. Therefore, we are piloting hrHPV self-testing in the community and implementing mobile a phone-based results notification system to facilitate follow up treatment at MRRH. The pilot study started September 17, 2017, and thus far 159 women have been screened. We are hopeful, that this study will bring innovative approaches (HRHPV self-sampling) to rural communities through health fairs, and use existing technologies, namely cell phones, to improve linkage to care for clinical follow up in women who otherwise do not access the health system.